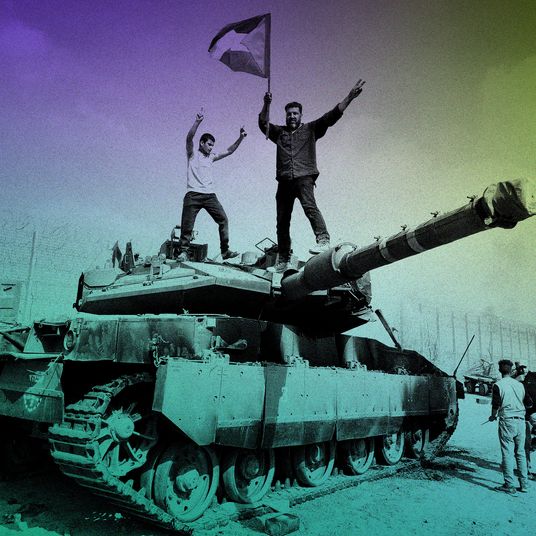

As the first accounts and images of last weekend’s Hamas attack in Israel filtered out into the world, each new detail suggesting worse to come, millions and eventually billions of people checked for updates on social media. What they found was both hellish and disorienting.

“Search for Israel or Hamas and you’ll find yourself in a cesspool of deepfake images, video-game clips presented as real-time footage, and straight-up lies,” wrote the Guardian’s Margaret Sullivan about X, formerly known as Twitter. The New York Times described social platforms as “flooded” with “false and misleading information, old and unrelated videos and photos with inaccurate claims, and fabricated assertions about the involvement of countries like the United States and Ukraine — adding confusion and deception to an already chaotic moment.” The European Union issued warnings to X, Meta, and TikTok to curb “propaganda” and “violent content,” which it suggested could be illegal under European law regardless of veracity.

This was all basically right and has remained so through the aftermath of Saturday’s attacks and into Israel’s retaliation. Social-media platforms have always broken down under pressure, often to the point of failure, but in recent years they have become noticeably less useful for understanding or even bearing witness to armed conflict. Critics this week singled out Elon Musk’s X, where moderation teams have been slashed and, the verification system has been dismantled, and a brazen new class of pay-for-play influencers has been rushing to monetize aggregated footage of the dead, as particularly degraded. This, too, is broadly correct and more glaring than other examples thanks to X’s perceived status as the de facto social network for news.

Beneath this perception, though, something bigger has shifted. The abundance of violent imagery on X is misleading. X’s role in collecting and disseminating raw, unfiltered, urgent content is in fact diminishing, and for reasons that predate Elon Musk and apply to other social-media platforms as well. Before Twitter became X, it had begun its transformation into a content aggregator — a downstream platform for monetizing content rather than a source, and outlet, for firsthand accounts of what’s happening in the world. Aric Toler of the New York Times and formerly of the online investigations group Bellingcat clocked the change during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when the chat app Telegram was the clear tool of choice for documenting, following, and propagandizing the war:

Telegram is a relatively uncensored platform without a central promotion mechanism. It’s the type of place where Hamas can maintain a large channel full of often violent content without affecting the experience of other users of the platform, where thousands of people can join channels full of combat videos posted by anonymous IDF soldiers, and, more immediately, where civilians in a war zone can share unfiltered media with the world and actionable information with one another. (Telegram’s CEO claims that “hundreds of thousands” of users in Israel and the Palestinian territories have signed up in recent days; many, in Gaza, are under bombardment or evacuation orders, and depending on the app for life-or-death updates.) Telegram is much closer to a purpose-built communications platform than social platforms ever were. Whether its policies are morally tenable — its founder, a billionaire Russian in exile, insists they are — it’s more practically sustainable, in the sense that users aren’t shown anything they don’t subscribe to (in contrast with, for example, the viral spread of mass-shooting livestreams on Facebook). One reason that users feel unusually disoriented on X — and Instagram, and Facebook, and YouTube, and TikTok — is because much of what they’re seeing is aggregated from a platform they’ve either never heard of or don’t use, without credit or context and with maximum engagement in mind.

A few words of caution here. The overwhelming focus on mis- and disinformation by mainstream-media organizations and governments is at best overblown and at worst censorious — note the conflation of “graphic” imagery with “disinformation” in the E.U.’s demands, which stress TikTok’s “particular obligation” to protect its young users. Disinformation is easy to denounce and has a capacious definition that makes it an ever-ready rhetorical refuge for governments and media organizations that are either conflicted about or implicated in its subjects. Nobody thinks it’s good that people are posting three-year-old videos of the Syrian civil war with the suggestion that they show Hamas rockets launched into Israel and the intent of making a quick buck, but we should be realistic about how much these things matter and where in the sequence of things they fall. As widely used as these platforms are, their policies, designs, and failures compound rather than create the fog of war. A better-run social media won’t fill the void left by a lack of electricity and communications capability on the ground in Gaza, for example. This war is not happening on X or Telegram.

Still, social media is a major channel through which people around the world have and will come to understand a conflict, and it’s worth understanding how information makes its way from war zones out into the world, how this process has changed, and the ways in which it’s been misunderstood.

Among the most valuable functions that social networks (exemplified by Twitter) offered, in the context of war in particular, was access to places, people, and perspectives that were otherwise not accessible to or deemed worthy of attention by traditional media and official sources. They were useful for surfacing and spreading novel information sourced directly from users, who could be anyone: victims or perpetrators of a massacre; soldiers or civilians on opposing sides of a war. At their best, social networks sat upstream from the rest of the media, providing publications, broadcasters, governments, and citizens with raw, verifiable, and often shocking and morally objectionable media and information and simultaneously forcing them to confront it.

This function, however, always represented a small part of what social media was for and was a huge pain for the companies that enabled it. Implicit in this week’s critiques of X et al. is a suggestion that social platforms were at one point generally and comprehensively good for understanding or following complicated, wrenching, disputed events, which is also not quite right. Social media services were not purpose-built citizen journalism machines. They were never especially adept at narrativizing, verifying, or contextualizing the information their users turned up. They were entertainment-oriented advertising products that enabled occasional revelatory alternative reporting and information-gathering while providing a means for spreading it. What made social-media platforms synonymous with the news over the past decade — the mass aggregation of all sorts of media, personal and public, into one place — was only tenuously connected to the phenomena described above.

Raw, firsthand, contested, multiparty accounts of conflicts presented obvious difficulties for commercial platforms, which gradually made them harder to share (the use of YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter by ISIS marked a turning point in how these platforms dealt with violent content in general). Platforms that still allow newsworthy war reporting tended to minimize its visibility, hiding it behind warnings and excluding it from recommendations — the gatekeeping instincts (or duties, depending on how you look at it) of mainstream conventional media replicated and effectively automated.

In recent years, all the major social-media platforms have evolved further into algorithmically driven TikTok-style recommendation engines. This sort of platform doesn’t preclude sharing firsthand accounts — see the numerous videos posted this week from southern Israel and Gaza — but it does complicate their use as tools for the straightforward recording and sharing of novel, controversial, disturbing, and potentially valuable firsthand accounts. Mainstream social media’s previous utility for newsgathering was incidental to its early strategy for growth, which was getting millions of people to make and share content for and with one another. Likewise, its loss of utility for news gathering is incidental to its next collective growth strategy, which replaces social sharing with algorithmic moderation and promotion.

The result is a generation of social-media platforms that is drifting a little further downstream from reality while remaining a crucial tool for its interpretation. In more mundane contexts, we might experience this change as frustration and alienation or with a sense of dull sense of irony, as formerly social networks build layer after layer of mediation between their users, who remain present but have become decreasingly aware of one another. In the context of war, we increasingly encounter either automated sanitization or, on a platform with slightly different guidelines, an uncanny spectacle of commercialized, decontextualized violence, detached from its sources and their reasons for sharing it in the first place.

These machines are technologically advanced but, in their centralized, top-down relationship with their users and content, they’re also becoming strikingly conventional —X’s loose moderation and Meta’s open aversion to “news” as a category are best understood as slightly different approaches to a similar algorithmic product. It’s a counterrevolutionary coda to the supposedly liberating era of the global town square, which social-media companies gave up on a long time ago anyway. And, for now, it’s the future of the news.

More on the israel-hamas war

- Israel-Hamas War Live Updates: Hundreds Dead After Blast at Gaza City Hospital

- DeSantis and Haley See Opening in Trump’s Israel Criticism

- ‘It’s Really Hard to Hold On in This Reality’