Sam Bankman-Fried is not a Stanford alum. Still, the disgraced ex–crypto wunderkind might as well be. He was raised in Silicon Valley’s techno-idealist training school by parents Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried, longtime professors at the law school. It’s this world that gave him credibility, helped him build his fortune, and provided him with an identity. “He was brought up as a utilitarian by his parents, two Stanford professors, is serious, dedicated, and committed to doing good,” reads an email sent by one of Bankman-Fried’s early proponents in Michael Lewis’s new book, Going Infinite. And when it was revealed that Bankman-Fried’s intentions were not, in fact, to do good, it was Stanford where he returned, under house arrest amid its bucolic palms.

Bankman-Fried, known universally as SBF, is the kind of fraud that Silicon Valley specializes in producing: the philosopher con artist. One of the most prominent proponents of effective altruism, he advocated doing the most good for the most number of people — or, in his case, making the most money possible in order to give it away. Stanford went mad for this story of an upstart entrepreneur trying to improve the world and making a killer fortune on the way. SBF lived the Stanford student’s dream, an eccentric visionary with a sprawling pad in the Bahamas and the adulation of the media and the markets alike.

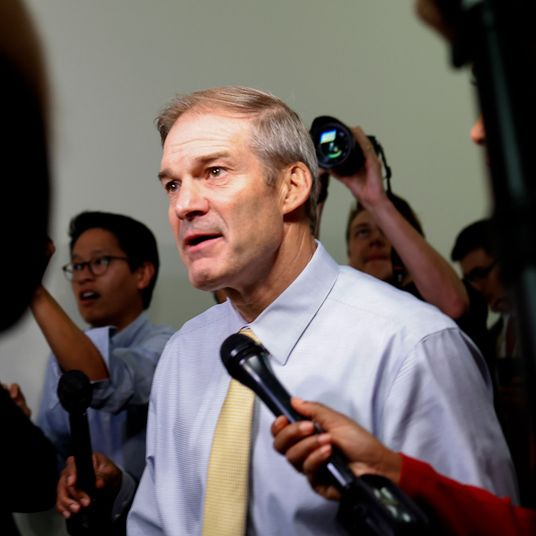

His undoing — playing out now in a federal courtroom in Manhattan, where Bankman-Fried is charged with wire fraud and money laundering — would seem to puncture those fantasies. And to some students, his story is a cautionary tale, the result of avarice and overambition. But for many people at Stanford, where I am a sophomore, it’s simply a laughing matter.

SBF’s trial is the capper to Stanford’s annus horribilis. Just weeks before he was indicted, fraudster Elizabeth Holmes was sentenced over her failed blood-test start-up, Theranos, which was founded using Stanford’s name as cachet and bankrolled by many a famous Stanford alum. Do Kwon, another Stanford alum, was arrested earlier this year for a multibillion-dollar crypto scheme. And Stan Cohen, an active Stanford professor, was found liable in court for tens of millions of dollars worth of fraud.

More than ever, it would seem Stanford is due for some serious introspection. Yet the one thing Silicon Valley seems incapable of is shaking off its own mythology.

Because his parents live in faculty housing, SBF became a bit of a campus curiosity. People would wander by the family’s home out of idle curiosity, sometimes even on dates. Over the past year, there have been several SBF-themed parties and sketch-comedy shows. And there is plenty of comedy to be found. Just months before his arrest, he had been invited to speak at a Stanford tech-ethics course. According to Lewis, SBF bragged about escaping oversight and avoiding traditional accounting, hubris that is laughable given the $8 billion that remains missing from FTX’s accounts.

But the gravity of his alleged crimes shouldn’t be understated. Lewis said in a 60 Minutes interview that the only people he hurt were “crypto speculators in the Bahamas” — as witness testimony has laid out during SBF’s criminal trial, this is blatantly untrue. Billions of dollars of customer funds were misappropriated, and now, at the end of it all, it’s pensioners, small-time investors, and more than a few kids my age left to foot the bill. Meanwhile, students at Stanford are wondering how they could achieve the same heights as him — just without the epic downfall.

It may be hard to imagine Bankman-Fried as a role model these days; he’s looked down on by pretty much everyone at this point (aside, perhaps, from Michael Lewis). But kids of my generation, and particularly the kids at Stanford, have been fed story after story about Silicon Valley and its infinite opportunities. Many grew up longing for Stanford and the access the school would give to that world. When they arrive, they treat the Stanford student body’s favorite movie, The Social Network, as a how-to guide in the same way that finance bros valorize the “Greed is good” speech from Oliver Stone’s Wall Street — which, to be clear, is about how greed is bad.

Lewis’s book, inadvertently, helps explain some of the dysfunction. Joe Bankman and Barbara Fried only “briefly attempted to inflict upon” SBF “a normal childhood before realizing that there was no point,” the book says. Instead, he was treated as a proto-adult, his ego flattered as his brilliance was proclaimed to Stanford dinner parties full of venerated guests — a poignant mirror image of how SBF would later be treated as an actual adult: a “child” billionaire, an innocent financial savant.

This is a childhood that may seem familiar to a lot of Stanford students. Many kids who come here have spent their whole lives believing that they are the next tech Jesus — they have what it takes to beat the odds and sit on top of the world. The emotional stuntedness of that sort of childhood reverberates around the Valley, where self-interest and egoism run amok. SBF neatly fits into that model; according to his on-and-off romantic partner (and, if prosecutors are to be believed, partner in fraud) Caroline Ellison, SBF believed he was going to be president of the United States one day. It is worth noting that Ellison, who says she helped misappropriate funds at SBF’s direction, is a Stanford alum.

The fraud cluster at Stanford — like the suicide clusters that wracked Silicon Valley a few years ago — is a product of culture. The warning signs have been there for years, but Stanford barreled past them. Now, with a spate of what our new president, Richard Saller, has called “fake it till you make it” actors, the decision to embrace Silicon Valley’s accelerationist mind-set has come back to bite.

Eleven years ago, Ken Auletta published an article in The New Yorker that called the school “Get Rich U” and delved into the conflict between education (the school’s ostensible purpose) and naked entrepreneurship, facilitated by venture capitalists who see the school as a hotbed for world-upending breakthroughs and get-rich-quick schemes alike. “There are no walls between Stanford and Silicon Valley,” he wrote. “Should there be?”

Some professors thought, and indeed some public commentators wrote, that this would engender a reckoning, that Stanford would finally have to think critically about the billions of dollars it hoovered up from the tech world. People feared that prospective students would no longer be interested in an institution that was tainted by so much lucre. But of course, the opposite was true. Stanford is harder to get into than ever before, its admissions rate more than 100 percent lower than it was in 2012. Meanwhile, its endowment is more than 100 percent larger.

But all that glitters is not gold, and the problems Auletta identified are even more pronounced now. Faculty and alumni have told me that the ouster of our former president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, over falsified research that I first reported last year for The Stanford Daily, has only furthered the uncertainty that lingers around Stanford and its culture. “It’s just so much bad news, every day,” one faculty senator was heard whispering to a colleague, as I reported in August.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Silicon Valley is young, not just in the makeup of its prodigy entrepreneurs and on-the-rise start-ups but in a more fundamental way: The power it has come to wield culturally and economically has only belonged to it for a handful of decades. As a direct consequence, it has yet to develop the systems of accountability and transparency that provide guardrails for other powerful institutions. The next saga in the Silicon Valley story will be focused less on accruing power and more on holding it accountable; it will be more about SBF’s fall than his rise.