This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

I was born in 1958, and like many of my generation, my parents had experienced a world in which Jews were murdered, brutalized, and abandoned. My father knew his mother and father to have been helpless peasants living under pogroms and without rights in the Russian Pale of Settlement. On my mother’s side, my laundry-worker grandmother was financially unable to save her two brothers and two sisters in Poland from extermination. My parents raised me with the idea that Jews were people who sided with the oppressed and worked their way into helping professions.

They could not adjust the worldview born of this experience to a new reality: that in Israel, we Jews had acquired state power and built a highly funded militarized society, and were now subordinating others. No one wants to think about themselves that way. As a Jew and an American who has gone through the complex, painful, and transforming process of facing the injustice against Palestinians committed in my name and with my tax dollars, I have had to change my self-concept. I have had to deprogram myself from the idea that Jews continued to be victims when, in some cases, we had become perpetrators.

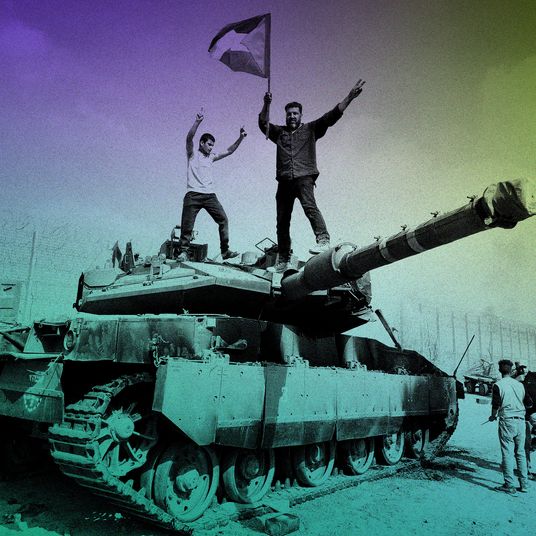

This shift in perception would have been unbearable for my parents. The idea that Jewish soldiers could march into villages and commit atrocities was incomprehensible. Yet, for 75 years, Palestinians have been murdered, incarcerated, and displaced with escalating violence by Israeli soldiers, and more recently by settlers. On October 7, these unending, untenable conditions exploded when Hamas broke through Israel’s imposed barriers. They reentered the land they consider home. They attacked formerly Palestinian villages and cities, now under the control of Israel. After decades of being on the receiving end of highly organized violence, they switched roles and became the murderers and kidnappers of more than 1,300 Israeli children and adults.

Among political and institutional leaders, there has been a collective refusal to see this horrible violence as the consequence of consistent, unending brutality — paid for by the United States in billions of dollars in aid to Israel per year. Instead, a familiar fog has overtaken so many. They pretend these decades of injustice never took place. That Gazans were not forced against their will to live under siege. That instead, a group of them suddenly — out of nowhere and with no history or experience — emerged as monsters and murdered people who had never hurt them in the past and held no threat over their future.

Selective recognition is the way we maintain our own sense of goodness. Today, we see this process of denial in every aspect of our lives. In this moment, it has become a tool to justify the sustained murder of thousands in Gaza, where the current death toll sits at over 2,600 people. As Israel began its relentless retaliation last week, an accompanying image of Israeli and American moral cleanliness was put swiftly into action. This is called “manufactured consent” — Noam Chomsky’s term for a system-supported propaganda by which authorities and media agree on a simplified reality, and it becomes the assumptive truth. We’ve seen this erasure of history in the uniform responses by western world leaders, university administrations, heads of foundations, and even book fairs over the past week. President Biden called Hamas’s attack “an act of sheer evil” without acknowledging the decades of colonial repression that make this violence legible. Instead he summoned another history, saying, “This attack has brought to the surface painful memories and the scars left by a millennia of antisemitism and genocide of the Jewish people.” He then assured Israel it could count on the United States’ military support, as though having been through genocide entitled them to commit it.

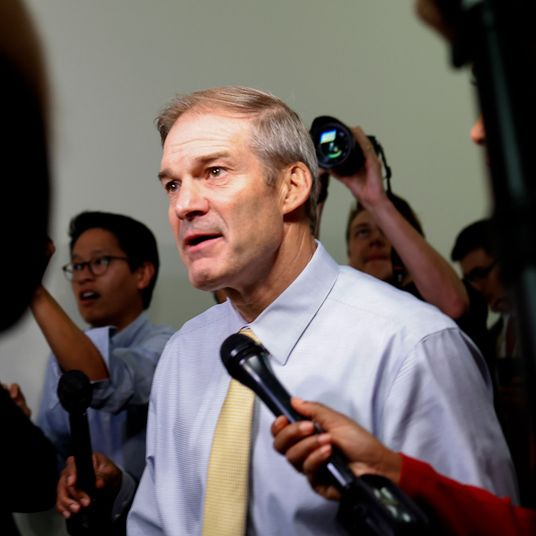

Nikki Haley, a former United Nations ambassador under Trump, might be Biden’s political opponent for the presidency, but she reinforced his claim of American-Israeli righteousness when she announced that “Israel needs our help in this battle of good vs. evil.” This is the binary that has set the tone: We are pure, that is to say that we have done everything exactly right and do not have to question ourselves. Last Tuesday, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre took a question from journalist Phil Wegmann. He asked her about the president’s attitude toward members of Congress who connect Palestinian violence to the Israeli violence that preceded it and have called for a cease-fire. Jean-Pierre replied, “We believe they are wrong, we believe they’re repugnant, and we believe they’re disgraceful.” Here we have a new equation: To ask for the ceasing of bombing and killing thousands of people is not a reasonable thought to consider. Instead, to stop killing is repulsive. To stop killing is a national disgrace.

Within this framework, any public outcry by Palestinians or allegiance with them becomes criminal. France and Germany banned people from showing compassion, solidarity, or pain for Palestinians in public marches. United Kingdom Home Secretary Suella Braverman called for monitoring displays of Palestinian flags. “At a time when Hamas terrorists are massacring civilians and taking the most vulnerable (including the elderly, women, and children) hostage, we can all recognize the harrowing effect that displays of their logos and flags can have on communities,” she said. Aside from the freedom-of-expression issues, there was a symbolic politics being deployed here. A flag that unites millions of Palestinians who live, not only in Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan, in refugee camps and in Israel, but in a global diaspora from Brooklyn and Detroit to London to the UAE — all of these people become unrepresentable.

This continues in the realm of education and ideas, where there have been visible examples of individual writers and anti-occupation groups arguing for context. On Friday, Semafor reported that MSNBC quietly removed three Muslim anchors from hosting duties, despite some at the network believing they had the most expertise on the conflict. Harper’s Bazaar editor Samira Nasr was forced to apologize for calling Israel’s move to cut power to Gaza “the most inhuman thing” she’s ever seen. The Frankfurt Book Fair rescinded an award it had chosen to give to Palestinian writer Adania Shibli. Donors have threatened the job of the president of the University of Pennsylvania because a literary festival called Palestine Writes took place there in September. Books, literature, ideas, discussion are all considered appropriate fodder to the manufacture of consent.

Humans want to be innocent. Better than innocent is the innocent victim. The innocent victim is eligible for compassion and does not have to carry the burden of self-criticism. Almost every person with authority or at the helm of an institution has declared that Israelis are innocent victims and that Palestinians are not. On 60 Minutes Sunday night, Biden reaffirmed his support for Israel while appearing to paint Palestinians as worthy of our compassion, too. He assured the American people that he was confident Israel would follow the “rules of war” and that “innocents in Gaza” would have “access to medicine and food and water.” But in the real world, Israel has cut off the flow of medicine, food, and water in Gaza. Water has already run out at U.N. shelters in the territory. Biden’s comments only reinforce that as far as the war is concerned, there are no innocents in Gaza.

At the root of this erasure is the increasing insistence that understanding history, looking at the order of events and the consequences of previous actions to understand why the contemporary moment exists as it does, somehow endorses the present. Explanations are not excuses — they are the illumination that builds the future. But the problem with understanding how we got to where we are is that we could then be implicated. And innocent victims cannot have any responsibility for creating the moment.

What is so ironic is that since 2005, Palestinians have been offering a nonviolent solution: the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement. Just as many of us grew up not buying grapes so that farmworkers could have a union or refusing to purchase South African products to help end apartheid, Palestinians have been asking the rest of us to put economic and cultural pressure on Israel through nonviolent boycott, to encourage them to move away from violent separation and toward negotiation and coexistence. The message here, too, was strategically twisted. The Israeli government and its supporters have led global campaigns to make supporting this boycott illegal. They have developed confusing worldwide messaging claiming that criticizing Israeli apartheid is the same thing as antisemitism. Every aspect of nonviolent organizing for a more equitable solution has been met with distortion as a tool of repression.

There is always, of course, the choice to end the siege of Gaza and the occupation of the West Bank and end the second-class reality of Palestinians living in Israel. Make everyone equal citizens with the same rights to vote, passports, roads, universities. The reason this solution of just reconciliation, known as “One State,” is not yet on the table is because of this selective reality: this panic that equalizing Palestinians in Israel would be allowing an enemy in, one that is fundamentally opposed to Israeli existence. But what this fear overlooks is that Palestine, like every society in the world, is a multidimensional society. Like Jews and Americans and Israelis, Palestinians contain multiple factions and religious perspectives — Muslim, Christian, Druse — and they hold a wide variety of political visions. The only thing they share is the desire to be free. They would never be able to act like a united block and all vote in the same way, for example, in the same way that we cannot. Because they are human, as we know ourselves to be. To fear unanimity is to imagine they are different from everyone else on earth.

The most difficult challenge in our lives is to face our contributions to the systems that reproduce inequality and consequential cycles of violence. Every person has to face their own complicities, and we start this by listening to whoever is suffering. Even if it is by our own hand. It is this transcendence that can lead us all to a better place.

More on the israel-hamas war

- Israel-Hamas War Live Updates: Hundreds Dead After Blast at Gaza City Hospital

- DeSantis and Haley See Opening in Trump’s Israel Criticism

- ‘It’s Really Hard to Hold On in This Reality’